Jack Reacher 15 - Worth Dying For Read online

Page 13

Reacher dressed again and all three of them took mugs of fresh coffee to the living room, which was a narrow rectangular space with furniture arranged in an L shape along two walls, and a huge flat screen television on a third wall. Under the screen was a rack loaded with audiovisual components all interconnected with thick wires. Flanking the screen were two serious loudspeakers. Set into the fourth wall was an undraped picture window that gave a great view of a thousand acres of absolutely nothing at all. Dormant lawn, the postand-rail fence, then dirt all the way to the horizon. No hills, no dales, no trees, no streams. But no trucks or patrols, either. No activity of any kind. Reacher took an armchair where he could see the door and the view both at the same time. The doctor sat on a sofa. His wife sat next to him. She didn’t look enthusiastic about talking.

Reacher asked her, “How old were you when Dorothy’s kid went missing?”

She said, “I was fourteen.”

“Six years older than Seth Duncan.”

“About.”

“Not quite in his generation.”

“No.”

“Do you remember when he first showed up?”

“Not really. I was ten or eleven. There was some talk. I’m probably remembering the talk, rather than the event.”

“What did people say?”

“What could they say? No one knew anything. There was no information. People assumed he was a relative. Maybe orphaned. Maybe there had been a car wreck in another state.”

“And the Duncans never explained?”

“Why would they? It was nobody’s business but theirs.”

“What happened when Dorothy’s little girl went missing?”

“It was awful. Almost like a betrayal. It changed people. A thing like that, OK, it puts a scare in you, but it’s supposed to have a happy ending. It’s supposed to turn out right. But it didn’t.”

“Dorothy thought the Duncans did it.”

“I know.”

“She said you stood by her.”

“I did.”

“Why?”

“Why not?”

Reacher said, “You were fourteen. She was what? Thirty? Thirty-five? More than twice your age. So it wasn’t about solidarity between two women or two mothers or two neighbors. Not in the normal sense. It was because you knew something, wasn’t it?”

“Why are you asking?”

“Call it professional interest.”

“It was a quarter of a century ago.”

“It was yesterday, as far as Dorothy is concerned.”

“You’re not from here.”

“I know,” Reacher said. “I’m on my way to Virginia.”

“So go there.”

“I can’t. Not yet. Not if I think the Duncans did it and got away with it.”

“Why does it matter to you?”

“I don’t know. I can’t explain it. But it does.”

“The Duncans get away with plenty, believe me. Every single day.”

“But I don’t care about that other stuff. I don’t care who gets their harvest hauled or when or how much they pay for it. You all can take care of that for yourselves. It’s not rocket science.”

The doctor’s wife said, “I was the Duncans’ babysitter that year.”

“And?”

“They didn’t really need one. They rarely went out. Or actually they went out a lot, but then they came right back. Like a trick or a subterfuge. Then they would be real slow about driving me home. It was like they were paying me to be there with them. With all four of them, I mean, not just with Seth.”

“How long did you work for them?”

“About six times.”

“And what happened?”

“In what way?”

“Anything bad?”

She looked straight at him. “You mean, was I interfered with?”

He asked, “Were you?”

“No.”

“Did you feel in any danger?”

“A little.”

“Was there any inappropriate behavior at all?”

“Not really.”

“So what was it made you stand by Dorothy when the kid went missing?”

“Just a feeling.”

“What kind of a feeling?”

“I was fourteen, OK? I didn’t really understand anything. But I knew I felt uncomfortable.”

“Did you know why?”

“It dawned on me slowly.”

“What was it?”

“They were disappointed that I wasn’t younger. They made me feel I was too old for them. It creeped me out.”

“You felt too old for them at fourteen?”

“Yes. And I wasn’t, you know, very mature. I was a small girl.”

“What did you feel would have happened if you had been younger?”

“I really don’t want to think about it.”

“And you told the cops about how you felt?”

“Sure. We all told them everything. The cops were great. It was twenty-five years ago, but they were very modern. They took us very seriously, even the kids. They listened to everybody. They told us we could say anything, big or small, important or not, truth or rumor. So it all came out.”

“But nothing was proved.”

The doctor’s wife shook her head. “The Duncans were clean as a whistle. Pure as the driven snow. I’m surprised they didn’t get the Nobel Prize.”

“But still you stood by Dorothy.”

“I knew what I felt.”

“Did you think the investigation was OK?”

“I was fourteen. What did I know? I saw dogs and guys in FBI jackets. It was like a television show. So, yes, I thought it was OK.”

“And now? Looking back?”

“They never found her bike.”

The doctor’s wife said that most farm kids started driving their parents’ beat-up pick-up trucks around the age of fifteen, or even a little earlier, if they were tall enough. Younger or shorter than that, they rode bikes. Big old Schwinn cruisers, baseball cards in the spokes, tassels on the handlebars. It was a big county. Walking was too slow. The eight-year-old Margaret had ridden away from the house Reacher had seen, down the track Reacher had seen, all knees and elbows and excitement, on a pink bicycle bigger than she was. Neither she nor the bike was ever seen again.

The doctor’s wife said, “I kept on expecting them to find the bike. You know, maybe on the side of a road somewhere. In the tall grass. Just lying there. That’s what happens on the television shows. Like a clue. With a footprint, or maybe the guy had dropped a piece of paper or something. But it didn’t happen that way. Everything was a dead end.”

“So what was your bottom line at the time?” Reacher asked. “On the Duncans. Guilty or not guilty?”

“Not guilty,” the woman said. “Because facts are facts, aren’t they?”

“Yet you still stood by Dorothy.”

“Partly because of the way I felt. Feelings are different than facts. And partly because of the aftermath. It was horrible for her. The Duncans were very self-righteous. And people were starting to wake up to the power they had over them. It was like the thought police. First Dorothy was supposed to apologize, which she wouldn’t, and then she was supposed to just shut up and carry on like nothing had ever happened. She couldn’t even grieve, because somehow that would have been like accusing the Duncans all over again. The whole county was uneasy about it. It was like Dorothy was supposed to take one for the team. Like one of those old legends, where she had to sacrifice her child to the monster, for the good of the village.”

There was no more talk. Reacher collected the three empty coffee cups and carried them out to the kitchen, partly to be polite, partly because he wanted to check the view through a different window. The landscape was still clear. Nothing coming. Nothing happening. After a minute the doctor joined him in the room, and asked, “So what are you going to do now?”

Reacher said, “I’m going to Virginia.”

“OK.”

“With two stops along the way.”

“Where?”

“I’m going to drop in on the county cops. Sixty miles south of here. I want to see their paperwork.”

“Will they still have it?”

Reacher nodded. “A thing like that, lots of different departments cooperating, everyone on their best behavior, they’ll have built a pretty big file. And they won’t have junked it yet. Because technically it’s still an open case. Their notes will be in storage somewhere. Probably a whole cubic yard of them.”

“Will they let you see them? Just like that?”

“I was a cop of sorts myself, thirteen years. I can usually talk my way past file clerks.”

“Why do you want to see it?”

“To check it for holes. If it’s OK, I’ll keep on running. If it’s not, I might come back.”

“To do what?”

“To fill in the holes.”

“How will you get down there?”

“Drive.”

“Showing up in a stolen truck won’t help your cause.”

“It’s got your plates on it now. They won’t know.”

“My plates?”

“Don’t worry, I’ll swap them back again. If the paperwork’s OK, then I’ll leave the truck right there near the police station with the proper plates on it, and sooner or later someone will figure out whose it is, and word will get back to the Duncans, and they’ll know I’m gone for good, and they’ll start leaving you people alone again.”

“That would be nice. What’s your second stop?”

“The cops are the second stop. First stop is closer to home.”

“Where?”

“We’re going to drop in on Seth Duncan’s wife. You and me. A house call. To make sure she’s healing right.”

Chapter 25

The doctor was immediately dead set against the idea. It was a house call he didn’t want to make. He looked away and paced the kitchen and traced his facial injuries with his fingertips and pursed his lips and ran his tongue over his teeth. Then eventually he said, “But Seth might be there.”

Reacher said, “I hope he is. We can check he’s healing right, too. And if he is, I can hit him again.”

“He’ll have Cornhuskers with him.”

“He won’t. They’re all out in the fields, looking for me. The few that remain, that is.”

“I don’t know about this.”

“You’re a doctor. You took an oath. You have obligations.”

“It’s dangerous.”

“Getting out of bed in the morning is dangerous.”

“You’re a crazy man, you know that?”

“I prefer to think of myself as conscientious.”

Reacher and the doctor climbed into the pick-up truck and headed back to the county two-lane and turned right. They came out on the road a couple of miles south of the motel and a couple of miles north of the three Duncan houses. Two minutes later the doctor stared at them as they passed by. Reacher took a look, too. Enemy territory. Three white houses, three parked vehicles, no obvious activity. By that point Reacher assumed the second Brett had delivered his messages. He assumed they had been heard and then immediately dismissed as bravado. Although the burned-out truck should have counted for something. The Duncans were losing, steadily and badly, and they had to know it.

Reacher made the left where he had the night before in the Subaru wagon, and then he threaded through the turns until Seth Duncan’s house appeared ahead on his right. It looked much the same lit by daylight as it had by electricity. The white mailbox with Duncan on it, the hibernating lawn, the antique horse buggy. The long straight driveway, the outbuilding, the three sets of doors. This time two of them were standing open. The back ends of two cars were visible in the gloom inside. One was a small red sports car, maybe a Mazda, very feminine, and the other was a big black Cadillac sedan, very masculine.

The doctor said, “That’s Seth’s car.”

Reacher smiled. “Which one?”

“The Cadillac.”

“Nice car,” Reacher said. “Maybe I should go smash it up. I’ve got a wrench of my own now. Want me to do that?”

“No,” the doctor said. “For God’s sake.”

Reacher smiled again and parked where he had the night before and they climbed out together and stood for a moment in the chill. The cloud was still low and flat, and mist was peeling off the underside of it and drifting back down to earth, ready for afternoon, ready for evening. The mist made the air itself look visible, gray and pearlescent, shimmering like a fluid.

“Showtime,” Reacher said, and headed for the door. The doctor trailed him by a yard or two. Reacher knocked and waited and a long minute later he heard feet on the boards inside. A light tread, slow and a little hesitant. Eleanor.

She opened up and stood there, with her left hand cupping the edge of the door and her right-hand fingers spidered against the opposite wall, as if she needed help with stability, or as if she thought her horizontal arm was protecting the inside of the house from the outside. She was wearing a black skirt and a black sweater. No necklace. Her lips had scabbed over, dark and thick, and her nose was swollen, the white skin tight over yellow contusions that were not quite hidden by her makeup.

“You,” she said.

“I brought the doctor,” Reacher said. “To check on how you’re doing.”

Eleanor Duncan glanced at the doctor’s face and said, “He looks as bad as I do. Was it Seth? Or one of the Cornhuskers? Either way, I apologize.”

“None of the above,” Reacher said. “It seems we have a couple of tough guys in town.”

Eleanor Duncan didn’t answer that. She just took her right hand off the wall and trailed it through a courtly gesture and invited them in. Reacher asked, “Is Seth home?”

“No, thank goodness,” Eleanor said.

“His car is here,” the doctor said.

“His father picked him up.”

Reacher asked, “How long will he be gone?”

“I don’t know,” Eleanor said. “But it seems they have much to discuss.” She led the way to the kitchen, where she had been treated the night before, and maybe on many previous occasions. She sat down in a chair and tilted her face to the light. The doctor stepped up and took a look. He touched the wounds very lightly and asked questions about pain and headaches and teeth. She gave the kind of answers Reacher had heard from many people in her situation. She was brave and somewhat self-deprecating. She said yes, her nose and mouth still hurt a little, and yes, she had a slight headache, and no, her teeth didn’t feel entirely OK. But her diction was reasonably clear and she had no loss of memory and her pupils were reacting properly to light, so the doctor was satisfied. He said she would be OK.

“And how is Seth?” Reacher asked.

“Very angry at you,” Eleanor said.

“What goes around comes around.”

“You’re much bigger than him.”

“He’s much bigger than you.”

She didn’t answer. She just looked at Reacher for another long second, and then she looked away, seemingly very unsure of herself, an expression of complete uncertainty on her face, its extent limited only by the immobility caused by the stiff scabs on her lips and the frozen ache in her nose. She was hurting bad, Reacher thought. She had taken two blows, he figured, probably the first to her nose and the second aimed lower at her mouth. The first had been hard enough to do damage without breaking the bone, and the second had been hard enough to draw blood without smashing her teeth.

Two blows, carefully aimed, carefully calculated, carefully delivered.

Expert blows.

Reacher said, “It wasn’t Seth, was it?”

She said, “No, it wasn’t.”

“So who was it?”

“I’ll quote your earlier conclusion. It seems we have a couple of tough guys in town.”

“They were here?”

“Twice.”

“Why?”

“I don’t know.”

“Who are they?”

“I don’t know.”

“They’ve been saying they represent the Duncans.”

“Well, they don’t. The Duncans don’t need to hire people to beat me. They’re perfectly capable of doing that themselves.”

“How many times has Seth hit you?”

“A thousand, maybe.”

“That’s good. Not from your point of view, of course.”

“But good from the point of view of your own clear conscience?”

“Something like that.”

She said, “Have at Seth all you like. All day, every day. Beat him to a pulp. Break every bone in his body. Be my guest. I mean it.”

“Why do you stay?”

“I don’t know,” she said. “Whole books have been written on that subject. I’ve read most of them. Ultimately, where else would I go?”

“Anywhere else.”

“It’s not that simple. It never is.”

“Why not?”

“Trust me, OK?”

“So what happened?”

She said, “Four days ago two men showed up here. They had East Coast accents. They were kind of Italian. They were wearing expensive suits and cashmere overcoats. Seth took them into his den. I didn’t hear any of the discussion. But I knew we were in trouble. There was a real animal stink in the house. After twenty minutes they all trooped out. Seth was looking sheepish. One of the men said their instructions were to hurt Seth, but Seth had bargained it down to hurting me. At first I thought I was going to be raped in front of my husband. That was what the atmosphere was like. The animal stink. But, no. Seth held me in front of him and they took turns hitting me. Once each. Nose, and then mouth. Then yesterday evening they came back and did all the same things over again. Then Seth went out for a steak. That’s what happened.”

“I’m very sorry,” Reacher said.

“So am I.”

“Seth didn’t tell you who they were? Or what they wanted?”

“No. Seth tells me nothing.”

“Any ideas?”

“They were investors,” she said. “I mean, they were here on behalf of investors. That’s the only sense I can make out of it.”

“Duncan Transportation has investors?”

“I suppose so. I imagine it’s not a wonderfully profitable business. Gas is very expensive right now, isn’t it? Or diesel, or whatever it is they use. And it’s wintertime, which must hurt their cash flow. There’s nothing to haul. Although, really, what do I know? Except that they’re always complaining about something. And I see on the news that apparently ordinary banks are difficult right now, for small businesses. So maybe they had to find a loan through unconventional sources.”

Die Trying

Die Trying Killing Floor

Killing Floor Persuader

Persuader Tripwire

Tripwire Running Blind

Running Blind Worth Dying For

Worth Dying For One Shot

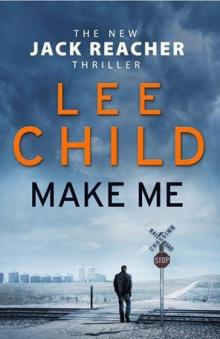

One Shot Make Me

Make Me The Midnight Line

The Midnight Line Bad Luck and Trouble

Bad Luck and Trouble 61 Hours

61 Hours Gone Tomorrow

Gone Tomorrow Night School

Night School Personal

Personal Never Go Back

Never Go Back MatchUp

MatchUp A Wanted Man

A Wanted Man Not a Drill

Not a Drill Echo Burning

Echo Burning Small Wars

Small Wars Deep Down

Deep Down The Hard Way

The Hard Way The Sentinel

The Sentinel The Sentinel (Jack Reacher)

The Sentinel (Jack Reacher) High Heat

High Heat Nothing to Lose

Nothing to Lose The Enemy

The Enemy The Affair

The Affair Second Son

Second Son Without Fail

Without Fail Too Much Time

Too Much Time The Hero

The Hero Blue Moon

Blue Moon The Christmas Scorpion

The Christmas Scorpion The Nicotine Chronicles

The Nicotine Chronicles The Fourth Man

The Fourth Man Deep Down_A Jack Reacher short story

Deep Down_A Jack Reacher short story The Essential Jack Reacher 12-Book Bundle

The Essential Jack Reacher 12-Book Bundle Gone Tomorrow jr-13

Gone Tomorrow jr-13 High Heat: A Jack Reacher Novella (jack reacher)

High Heat: A Jack Reacher Novella (jack reacher) High Heat_A Jack Reacher Novella

High Heat_A Jack Reacher Novella Jack Reacher 15 - Worth Dying For

Jack Reacher 15 - Worth Dying For Jack Reacher's Rules

Jack Reacher's Rules No Middle Name

No Middle Name 14 61 Hours

14 61 Hours First Thrills, Volume 3

First Thrills, Volume 3 Jack Reacher 01 - Killing Floor

Jack Reacher 01 - Killing Floor The Affair: A Reacher Novel

The Affair: A Reacher Novel FaceOff

FaceOff Good and Valuable Consideration

Good and Valuable Consideration Mystery Writers of America Presents Vengeance

Mystery Writers of America Presents Vengeance Jack Reacher 20 - Make Me

Jack Reacher 20 - Make Me Not a Drill: A Jack Reacher Short Story

Not a Drill: A Jack Reacher Short Story 17 A Wanted Man

17 A Wanted Man James Penney's New Identity/Guy Walks Into a Bar

James Penney's New Identity/Guy Walks Into a Bar Vengeance: Mystery Writers of America Presents

Vengeance: Mystery Writers of America Presents Lee Child's Jack Reacher Books 1-6

Lee Child's Jack Reacher Books 1-6 Killer Year

Killer Year Personal (Jack Reacher 19)

Personal (Jack Reacher 19) The Essential Jack Reacher 10-Book Bundle

The Essential Jack Reacher 10-Book Bundle First Thrills

First Thrills Echo Burning jr-5

Echo Burning jr-5 Good and Valuable Consideration_Jack Reacher vs. Nick Heller

Good and Valuable Consideration_Jack Reacher vs. Nick Heller A Wanted Man: (Jack Reacher 17)

A Wanted Man: (Jack Reacher 17) 23 Past Tense

23 Past Tense First Thrills, Volume 4

First Thrills, Volume 4 Small Wars_A Jack Reacher Story

Small Wars_A Jack Reacher Story