FaceOff Read online

Page 2

Detective Zebrowski shrugged. “You think d-bags like Lonnie Cullen think things through before they do them? If they did, they wouldn’t know the number on their orange jumpsuits better than their own birthdays. He did it because he’s a criminal and he’s an idiot and he has less impulse control than a flea at a livestock auction.”

“And the boyfriend angle?”

“Looking into it.”

Two nights ago Dontelle said to Patrick, “But you don’t believe it?”

Patrick shrugged. “Deadbeat dads dodge their kids, they don’t kidnap ’em, not the ones who’ve been out of the picture as long as Lonnie has. As for the boyfriend theory, she’s, what, shacked up with him for three days, they never go out to grab a bite, call a friend?”

“All I know,” Dontelle said, “is she seemed like a sweet kid. Not one of them typical project girls who’s always frontin’, talkin’ shit. She was quiet but . . . considerate, you know?”

Patrick took another drink of beer. “No. Tell me.”

“Well, you get a job like mine, you got to do a probation period—ninety days during which they can shitcan you without cause. After that, you with the city, man, gotta fuck up huge and be named Bin Laden for the city be able to get rid of your ass. I hit my ninety a couple weeks ago and not only did Chiffon congratulate me, she gave me a cupcake.”

“No shit?” Patrick smiled.

“Store bought,” Dontelle said, “but still. How sweet is that?”

“Pretty sweet.” Patrick nodded.

“You’ll see in about twelve years with your kid, they ain’t too into thinking about others at that age. It’s all about what’s going on up here”—he tapped his head—“and down there”—he pointed at his groin.

They drank in silence for a minute.

“Nothing else you remember about that day? Nothing out of the ordinary?”

He shook his head. “Just a day like any other—‘See you tomorrow, Chiffon,’ and she say, ‘See you tomorrow, Dontelle.’ And off she walk.”

Patrick thanked him and paid for the drinks. He was scooping his change off the bar when he said, “You had a probationary period?”

Dontelle nodded. “Yeah, it’s standard.”

“No, I know, but I guess I was wondering why you started so late in the school year. I mean, it’s May. Means you started in, what, February?”

Another nod. “End of January, yeah.”

“What’d you do before that?”

“Drove a tour bus. Drove from here to Florida, here to Montreal, here to P-Town, all depended on the season. Hours were killing me. Shit, the road was killing me. This job opened up, I jumped.”

“Why’d it open up?”

“Paisley got a duey.”

“Paisley?”

“Guy I replaced. Other drivers told me he was a piece of work, man. Show up with forty kids in his charge, eyes all glassy. Even the union wouldn’t protect him after the last time. Drove the bus off the side of the American Legion Highway, right?” Dontelle was laughing in disbelief. “Damn near tipped it. Gets out to take a piss. This is at six thirty in the ante meridiem, feel me? He gets back in, tries to pull back off the shoulder, but now the bus does tip. That’s Lawsuit City there, man. Forty times over.”

“Paisley,” Patrick said.

“Edward Paisley,” Dontelle said, “like the ties.”

PAISLEY LIVED ON WYMAN STREET in a gray row house with fading white trim. There was a front porch with an old couch on it. Bosch drove by the place and then circled the block and went by again before finding a parking space at the curb a half block away. By adjusting his side-view mirror he had a bead on the front door and porch. He liked doing one-man surveillances this way. If somebody was looking for a watcher they usually checked windshields. Parking with his back to his target made him harder to see. Edward Paisley may have had nothing to do with the murder of Letitia Williams all those years ago. But if he did, he hadn’t survived the last fifteen years without checking windshields and being cautious.

All Bosch was hoping for, and that he’d be happy with, was to see some activity at the home to confirm that Paisley was at the address. If he got lucky, Paisley would go out and grab a cup of coffee or a bite to eat at lunch. Bosch would be able to get all the DNA he’d need off a discarded cup or a pizza crust. Maybe Paisley was a smoker. A cigarette butt would do the trick as well.

Harry pulled a file out of the locking briefcase he took on trips and opened it to look at the enlargement of the photo he’d pulled the day before from the Massachusetts DMV. It was taken three years earlier. Paisley was white, balding, and then fifty-three years old. He no longer had the driver’s license, thanks to the suspension that followed the DUI arrest four months ago. Paisley tipped a school bus and then blew a point-oh-two on the machine and with it blew his job with the school district and possibly his freedom. The arrest put his fingerprints into the system where they were waiting for Bosch. Sometimes Harry got lucky that way. If he had pulled the Williams case eleven months earlier and submitted the prints collected at the crime scene for electronic comparison there would have been no resulting match. But Bosch pulled the case four months ago and here he was in Boston.

Two hours into his surveillance Bosch had seen no sign of Paisley and was growing restless. Perhaps Paisley had left the house for the day before Bosch could set up on the street. Bosch could be wasting his time, watching an empty house. He decided to get out and do a walk-by. He’d seen a convenience store a block past the target address. He could walk by Paisley’s address, eyeball the place up close, then go down and pick up a newspaper and a gallon of milk. Back at the car he would pour the milk into the gutter and keep the jug handy if he had to urinate. It could be a long day watching the house.

The paper would come in handy as well. He’d be able to check the late baseball scores. The Dodgers had gone into extra innings the night before against the hated Giants and Bosch had gotten on the plane not knowing the game’s outcome.

But at the last moment Bosch decided to stay put. He watched a dinged-up Jeep Cherokee pull into a curbside slot directly across the street from his own position. There was a lone man in the car and what made Bosch curious was that he never got out. He stayed slumped a bit in his seat and appeared to be keeping an eye on the same address as Bosch.

Bosch could see he was on a cell phone when he first arrived but then for the next hour the man remained behind the wheel of his Jeep, simply watching the goings-on on the street. He was too young to be Paisley. Late thirties or early forties, wearing a baseball cap and a thin gray hoodie over a dark-blue graphic tee. Something about the cap gave Bosch pause until he realized it was the first one he’d seen in a city filled with them that didn’t have a B on it. Instead, it had what appeared to be a crooked smiley face on it, though Bosch couldn’t be positive from the other side of the street. It looked to Bosch like the guy was waiting for somebody, possibly the same somebody Bosch was waiting for.

Eventually, Bosch realized he had become a similar object of curiosity for the man across the street, who was now surreptitiously watching Bosch as Bosch was surreptitiously watching him.

They kept at this careful cross-surveillance until a siren split the air and a fire truck trundled down the road between them. Bosch tracked the truck in the side mirror and when he looked back across the street he saw that the Jeep was empty. The man had either used the distraction of the passing fire truck to slip out, or he was lying down inside.

Bosch assumed it was the former. He sat up straight and checked the street and the sidewalk across from him. No sign of anyone on foot. He turned to check the sidewalk on his own side and there at the passenger’s window was the guy in the baseball hat. He’d turned the hat backward, the way gang squad guys often did when they were on the move. Bosch could see a silver chain descending from the sides of his neck into his graphic tee, figured there was a badge hanging from it. Definitely a gun riding the back of the guy’s right hip, something boxy and b

igger than a Glock. The man bent down to put himself at eye level with Bosch. He twirled his finger at Bosch, a request to roll the window down.

THE GUY WITH THE HERTZ NeverLost GPS jutting off his dashboard looked at Patrick for a long moment, but then lowered his window. He looked like he was mid-fifties and in good shape. Wiry. Something about him said cop. The wariness in his eyes for one; cop’s eyes—you could never believe they truly closed. Then there was the way he kept one hand down in his lap so he could go inside the sport coat for the Glock or the Smith if it turned out Patrick was a bad guy. His left hand.

“Nice move,” he said.

“Yeah?” Patrick said.

The guy nodded over his shoulder. “Sending the fire truck down the street. Good distraction. You with District Thirteen?”

A true Bostonian always sounded like he was just getting over a cold. This guy’s voice was clean air; not light exactly but smooth. An out-of-towner. Not a trace of Beantown in that voice. Probably a fed. Minted in Kansas or somewhere, trained down in Quantico and then sent up here. Patrick decided to play along as long as he could. He tried to open the door but it was locked. The guy unlocked it, moved his briefcase to the backseat, and Patrick got in.

“You’re a bit away from Center Plaza, aren’t you?” Patrick said.

“Maybe,” he said. “Except I don’t know where or what Center Plaza is.”

“So you’re not with the bureau. Who are you with?”

The man hesitated again, kept that left hand in his lap, then nodded like he’d decided to take a flier.

“LAPD,” he said. “I was going to check in with you guys later today.”

“And what brings the LAPD out to JP?”

“JP?”

“Jamaica Plain. Can I see some ID?”

He pulled a badge wallet out and flipped it open so Patrick could study the detective’s badge and the ID. His name was Hieronymus Bosch.

“Some name you’ve got. How do you say that?”

“Harry’s good.”

“Okay. What are you doing here, Harry?”

“How about you? That chain around your neck isn’t attached to a badge.”

“No?”

Bosch shook his head. “I’d have seen the outline of it through your shirt. Crucifix?”

Patrick stared at him for a moment and then nodded. “Wife likes me to wear it.” He held out his hand. “Patrick Kenzie. I’m not a cop. I’m an independent contractor.”

Bosch shook his hand. “You like baseball, Pat?”

“Patrick.”

“You like baseball, Patrick?”

“Big-time. Why?”

“You’re the first guy I’ve seen in this town not wearing a Sox hat.”

Patrick pulled off his hat and considered the front of it as he ran a hand through his hair. “Imagine that. I didn’t even look when I left the house.”

“Is that a rule around here? You’ve all got to represent Red Sox Nation or something?”

“It’s not a rule, per se, more like a guideline.”

Bosch looked at the hat again. “Who’s the crooked smiley-faced guy?”

“Toothface,” Patrick said. “He’s, like, the logo, I guess, of a record store I like.”

“You still buy records?”

“CDs. You?”

“Yeah. Jazz mostly. I hear it’s all going to go away. Records, CDs, the whole way we buy music. MP3s and iPods are the future.”

“Heard that, too.” Patrick looked over his shoulder at the street. “We looking at the same guy here, Harry?”

“Don’t know,” Bosch said. “I’m looking at a guy for a murder back in nineteen-ninety. I need to get some DNA.”

“What guy?”

“Tell you what, why don’t I go over to District Thirteen and check in with the captain and make this all legit? I’ll identify myself, you identify yourself. A cop and a private eye working together to ease the burden of the Boston PD. Because I don’t want my captain back in LA catching a call from—”

“Is it Paisley? Are you watching Edward Paisley?”

He looked at Patrick for a long moment. “Who is Edward Paisley?”

“Bullshit. Tell me about the case from nineteen-ninety.”

“Look, you’re a private dick with no ‘need to know’ that I can see and I’m a cop—”

“Who didn’t follow protocol and check in with the local PD.” He craned his head around the car. “Unless there’s a D-thirteen liaison on this street who’s really fucking good at keeping his head down. I got a girl missing right now and Edward Paisley’s name popped up in connection to her. Girl’s twelve, Bosch, and she’s been out there three days. So I’d love to hear what happened back in nineteen-ninety. You tell me, I’ll be your best friend and everything.”

“Why is no one looking for your missing girl?”

“Who’s to say they’re not?”

“Because you’re looking and you’re private.”

Patrick got a whiff of something sad coming off the LA cop. Not the kind of sad that came from bad news yesterday but from bad news most days. Still, his eyes weren’t dead; they pulsed instead with appetite—maybe even addiction—for the hunt. This wasn’t a house cat who’d checked out, who kept his head down, took his paycheck, and counted the days till his twenty. This was a cop who kicked in doors if he had to, whether he knew what was on the other side or not, and had stayed on after twenty.

Patrick said, “She’s the wrong color, wrong caste, and there’s enough plausible anecdotal shit swirling around her situation to make anyone question whether she was abducted or just walked off.”

“But you think Paisley could be involved.”

Patrick nodded.

“Why?”

“He’s got two priors for sexual abuse of minors.”

Bosch shook his head. “No. I checked.”

“You checked domestic. You didn’t know to check Costa Rica and Cuba. Both places where he was arrested, charged, had the shit beat out of him, and ultimately bought his way out. But the arrests are on record over there.”

“How’d you find them?”

“I didn’t. Principal of Dearborn Middle School was getting a bad feeling about Paisley when he drove a bus for them. One girl said this, one boy said that, another girl said such and such. Nothing you could build a case on but enough for the principal to call Paisley into her office a couple times to discuss it.” Patrick pulled a reporter’s notebook from his back pocket, flipped it open. “Principal told me Paisley would have passed both interviews with flying colors but he mentioned milk one time too many.”

“Milk?”

“Milk.” Patrick looked up from his notes and nodded. “He told the principal during their first meeting—he’d already been working there a year; the principal doesn’t have shit to do with hiring bus drivers, that’s HR downtown—that she should smile more because it made him think of milk. He told her in the second meeting that the sun in Cuba was whiter than milk, which is why he liked Cuba, the white lording over everything and all. It stuck with her.”

“Clearly.”

“But so did the Cuba reference. It takes work to get to Cuba. You gotta fly to Canada or the Caribbean, pretend you banged around there when in fact you hopped a flight to Havana. So when her least favorite bus driver got a DUI while driving her students, she eighty-sixed his ass straightaway, but then started wondering about Cuba. She pulled his résumé and found gaps—six-month unexplained absence in eighty-nine, ten-month absence in ninety-six. Our friendly principal—and remember, Bosch, your principal is your pal—kept digging. Didn’t take long to find out that the six months in eighty-nine were spent in a Costa Rican jail, the ten months in ninety-six were spent in a cell in Havana. Plus, he moved around a lot in general—Phoenix, LA, Chicago, Philly, and, finally, Boston. Always drives a bus, and only has one known relative—a sister, Tasha. Both times he was released from foreign jails he was released into her custody. And I’m willing to bet she walked a bag of

cash onto her flight that she didn’t have with her on the flight back home. So now, now he’s here and Chiffon Henderson is not. And you know everything I know, Detective Bosch, but I bet you can’t say the same.”

Bosch leaned back against his seat hard enough to make the leather crackle. He looked over at Patrick Kenzie and told the story of Letitia Williams. She was fourteen years old and stolen from her bedroom in the night. No leads, few clues. The abductor had cut out the screen on her bedroom window. Didn’t remove the screen, frame and all. Cut the screen out of the frame with a razor and then climbed in.

The cut screen put immediate suspicion on the disappearance. The case was not shunted aside as a presumed runaway situation the way Chiffon Henderson’s would be fifteen years later. Detectives from the major crimes unit rolled that morning after the girl was discovered gone. But the abduction scene was clean. No trace evidence of any kind recovered from the girl’s bedroom. The presumption was the abductor or abductors had worn gloves, entered, and quickly incapacitated the girl, and just as quickly removed her through the window.

However, there was one piece of presumed evidence gathered outside the house on the morning of the initial investigation. In the alley that ran behind the home where Letitia Williams lived investigators found a flashlight. The first guess was that it had belonged to the abductor and it had inadvertently been dropped while the victim was carried to a waiting vehicle. There were no fingerprints on the flashlight as it was assumed the perpetrator had worn gloves. But an examination of the inside of the flashlight found two viable latent fingerprints on one of the batteries.

It was thought to be the one mistake that would prove the abductor’s undoing. But the thumb and forefinger prints were compared to those on file with the city and state and no match was found. The prints were then sent on to the FBI for comparison with prints in the bureau’s vast data banks, but again there was no hit and the lead died on the vine.

In the meantime, the body of Letitia Williams was found exactly one week after her abduction on a hillside in Griffith Park, right below the observatory. It appeared as though the killer had specifically chosen the location because the body would be spotted quickly in daylight hours by someone looking down from the observatory.

Die Trying

Die Trying Killing Floor

Killing Floor Persuader

Persuader Tripwire

Tripwire Running Blind

Running Blind Worth Dying For

Worth Dying For One Shot

One Shot Make Me

Make Me The Midnight Line

The Midnight Line Bad Luck and Trouble

Bad Luck and Trouble 61 Hours

61 Hours Gone Tomorrow

Gone Tomorrow Night School

Night School Personal

Personal Never Go Back

Never Go Back MatchUp

MatchUp A Wanted Man

A Wanted Man Not a Drill

Not a Drill Echo Burning

Echo Burning Small Wars

Small Wars Deep Down

Deep Down The Hard Way

The Hard Way The Sentinel

The Sentinel The Sentinel (Jack Reacher)

The Sentinel (Jack Reacher) High Heat

High Heat Nothing to Lose

Nothing to Lose The Enemy

The Enemy The Affair

The Affair Second Son

Second Son Without Fail

Without Fail Too Much Time

Too Much Time The Hero

The Hero Blue Moon

Blue Moon The Christmas Scorpion

The Christmas Scorpion The Nicotine Chronicles

The Nicotine Chronicles The Fourth Man

The Fourth Man Deep Down_A Jack Reacher short story

Deep Down_A Jack Reacher short story The Essential Jack Reacher 12-Book Bundle

The Essential Jack Reacher 12-Book Bundle Gone Tomorrow jr-13

Gone Tomorrow jr-13 High Heat: A Jack Reacher Novella (jack reacher)

High Heat: A Jack Reacher Novella (jack reacher) High Heat_A Jack Reacher Novella

High Heat_A Jack Reacher Novella Jack Reacher 15 - Worth Dying For

Jack Reacher 15 - Worth Dying For Jack Reacher's Rules

Jack Reacher's Rules No Middle Name

No Middle Name 14 61 Hours

14 61 Hours First Thrills, Volume 3

First Thrills, Volume 3 Jack Reacher 01 - Killing Floor

Jack Reacher 01 - Killing Floor The Affair: A Reacher Novel

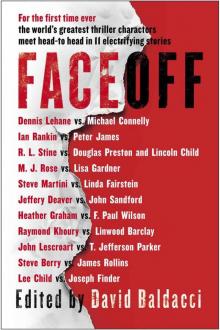

The Affair: A Reacher Novel FaceOff

FaceOff Good and Valuable Consideration

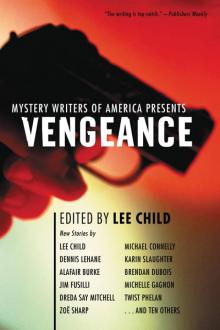

Good and Valuable Consideration Mystery Writers of America Presents Vengeance

Mystery Writers of America Presents Vengeance Jack Reacher 20 - Make Me

Jack Reacher 20 - Make Me Not a Drill: A Jack Reacher Short Story

Not a Drill: A Jack Reacher Short Story 17 A Wanted Man

17 A Wanted Man James Penney's New Identity/Guy Walks Into a Bar

James Penney's New Identity/Guy Walks Into a Bar Vengeance: Mystery Writers of America Presents

Vengeance: Mystery Writers of America Presents Lee Child's Jack Reacher Books 1-6

Lee Child's Jack Reacher Books 1-6 Killer Year

Killer Year Personal (Jack Reacher 19)

Personal (Jack Reacher 19) The Essential Jack Reacher 10-Book Bundle

The Essential Jack Reacher 10-Book Bundle First Thrills

First Thrills Echo Burning jr-5

Echo Burning jr-5 Good and Valuable Consideration_Jack Reacher vs. Nick Heller

Good and Valuable Consideration_Jack Reacher vs. Nick Heller A Wanted Man: (Jack Reacher 17)

A Wanted Man: (Jack Reacher 17) 23 Past Tense

23 Past Tense First Thrills, Volume 4

First Thrills, Volume 4 Small Wars_A Jack Reacher Story

Small Wars_A Jack Reacher Story