Personal (Jack Reacher 19) Read online

Page 31

And it was strong. The design brief was to survive a .50-calibre armour-piercing round, and the test procedure was meticulous and detailed. I read it very carefully. I could understand most of the language used, although some of it was highly technical and therefore unfamiliar. But numbers were the same the world over, and I could recognize 100 when I saw it. The test panels had scored 100 per cent against nine-millimetre handguns, and against .357 Magnums, and .44 Magnums, at ranges from fifty feet all the way down to contact shots, like Joey.

So then they flew the panels down to a place called Draguignan, in the south of France, near where my grandfather had stabbed the snake, where there was a huge military facility, with rifle ranges galore. They set up at three hundred feet, and the panels scored 100 per cent against .223 Remingtons and 7.62-millimetre NATO rounds. At which point the scientists doubled down. They must have been feeling good. They shortened the range to two hundred feet, which was unrealistically short for the larger calibres, and then they skipped right over worthy contenders like the .308 Winchester and the British .303, and went straight to the .44 Remington Magnum. From two hundred feet. Which was less than seventy yards. Like a battleship firing at the harbour wall.

The panels scored 100 per cent.

Then came the moment of truth. They loaded up the .50-cal and laid it on the bench. Armour-piercing ammunition. For which seventy yards was more than unrealistically short. But I understood the point they were hoping to make.

The panels scored 100 per cent.

And at a hundred feet, and at fifty, and even at twenty-five. Although the scientists were open enough to point out that the visible pitting at the shorter ranges would require replacement of the panels after every such incident. Even the scientists were political enough to understand a candidate couldn’t show up behind gear already riddled with bullet holes from previous failed attempts. Like he had gotten out of Dodge just in time. Not good for the image. People might get a clue.

There was a lot of foreign money in the project, and a lot of valuable foreign lives depending on the outcome, so the test procedure was supervised every step of the way by representatives from all the interested parties. They checked the numbers, they asked the questions, they looked behind the curtain. They were all intelligence specialists, but scientifically literate. The old guard, with nothing better to do, all extremely experienced. The guys from Paris didn’t mind. It was like any other peer review. Just compressed in time. I swiped the screen and scrolled down, through the list of participants, just a little ways, to E, for Etats-Unis d’Amérique.

The United States of America.

The Pentagon had sent Tom O’Day.

FIFTY-FOUR

I LOOKED OVER the low wall at Joey’s house. The gates were still open and lights were still burning. But nothing else was happening. I gave the phone back to Bennett, and I said, ‘Why don’t you go take a short stroll?’

He said, ‘Why would I want to?’

‘I need to talk to Ms Nice alone.’

‘What are you going to say to her?’

‘Something inaudible, from where you’re going to be.’

He paused a beat, and then he got up and disappeared in the dark, there one minute, gone the next, like on the apartment balcony in Paris. Nice and I squatted side by side, with our backs against the wall.

I said, ‘This is the scene where I try to get rid of you.’

She didn’t answer.

I said, ‘Not for the reasons you think. I could use your help a dozen different ways, and you’d be good at all of them. But this is between Kott and me. He wants me gone, therefore I want him gone. Not fair to involve other people, in a private quarrel. I’m going to tell Bennett the same thing.’

‘Bennett will stay away anyway. He has to. There are rules. But I’m free to do what I want.’

‘This is me and Kott. Which has rules too. It’s one on one.’

‘You’re just saying that.’

‘Because I mean it.’

‘I think you’re being kind.’

‘That’s an accusation I don’t hear often.’

She said, ‘Why did he take my pill?’

‘Take as in deprive, or take as in swallow?’

‘Swallow.’

‘I’m guessing he took all kinds of pills. A guy that big gets aches and pains. In his back, and his joints. So he already likes the opiates and the painkillers, and then he starts to dabble in the bad stuff passing through his hands. Pretty soon, he sees a pill, he takes it. Occupational hazard.’

‘I don’t want to take them any more. Did you see his mouth? He was disgusting.’

‘Right now you can’t take them any more. Even if you wanted to.’

‘Is that the reason? You think I’m going to freak out?’

‘Are you?’

‘Not from anxiety, anyway. I can’t even see anxiety in the rear-view mirror.’

‘We’ll be OK.’

‘We?’

‘You out here, me in there.’

‘I should help.’

‘This is me and Kott,’ I said again. ‘I’m not going to gang up on him. Wouldn’t feel right, afterwards.’

The gates were still open, but I didn’t want to go in the front. It was the obvious point of entry. It was the main place Kott would watch. Probably MI5 would come up with a number. Kott spent 61 per cent of his time watching the front. In second place would be the back yard. Third and fourth place would be the end walls. But which was third and which was fourth? I guessed third place went to the end facing the bowling club. That was where the action had been thus far. So I headed the other way, to the other end of the house, fourth place, away from the night-vision, creeping through the shadows, then climbing the fence. Which was not easy, but it was feasible, because the ironwork had sculpted features that acted like rungs on a ladder. I stepped down into a flowerbed. The side of the house was right there, across a narrow path. There were eight ground-floor windows. They would all have been drawn small by the kid with the crayon, but I could have gotten through any one of them standing up.

I checked the nearest window. The sill was chest-high to me. A small room. Relatively speaking. A nook or a niche or a parlour. Or a library or an office or a sitting room. I moved on to the next window. Through which was a hallway. Which was much better. There was the foot of a staircase visible, about thirty-five feet away. I guessed the hallway turned ninety degrees to the right at some point, to reach the front door.

I stood still and took a breath. In, and out. Then again. Then I used the butt of the captured Browning, and I broke the window, smash, smash, smash, all the glass I could reach, until the hole was big enough to climb through. I figured Kott would instantly see it as a bluff. No more than a diversion. As in, he was supposed to investigate, and meanwhile I would come in the front door, behind him. He would predict that. So he would go guard the front door instead. Except he was professionally paranoid, so just as instantly he would call it a double bluff, and he would head for the window as planned, to meet me head-on. So I triple-bluffed him. I sprinted for the front. I knew the door was open. That kind of a lock, you have to stop and use the key, both ways, out as well as in. And the departing guards hadn’t. They had gotten straight in the Jaguar, and hit the gas, no delay at all, putting on their coats, and slicking down their hair.

The door handle was a grand affair, a neat Georgian style swelled up to about thirty inches tall. The lever I turned was the size of most people’s forearms. Inside I saw a lobby with black and white marble on the floor, and a chandelier the size of an apple tree.

No sign of Kott.

Which was good. It let me open the door all the way, for an unrestricted field of fire. Behind the lobby was a long section of hallway, with the staircase at the far end, which meant the part of the hallway with the busted window was on the left, at ninety degrees.

I stepped inside.

No sign of Kott.

Which meant if he had only doubled where I had

tripled, he was right then staring at the broken glass, or searching room to room in the immediate vicinity, through all the pesky nooks and niches and parlours and libraries and offices and sitting rooms.

He was on my left, at ninety degrees.

I walked through the lobby to the hallway. Like any other hallway it was rectangular, much longer than it was wide, with hallway-style furniture, with doors left and right, to the kind of rooms that big houses always seemed to have. But I had been in big houses before, and Joey’s place didn’t feel like any of them. I remembered doors that looked way further apart than normal, implying huge rooms beyond, which turned out to look even bigger than expected, mostly because the walls went on and on, as if the room was saying, You know I’m big, because my walls go on for ever. Proportion, in other words. Joey’s place really was a regular house all swollen up in perfect lock step. The rooms were huge, but they didn’t look it, because the doors were the regular distance apart, except the doors were more than nine feet tall, more than ten with the architrave frames, so the regular distance was an optical illusion.

The marble squares on the floor would have been two feet on a side in any designer magazine, but in Joey’s house they were three. A full yard. The baseboards would have been twelve inches high in a fancy Victorian place. In Joey’s house they were a full foot and a half. A regular door knob would hit me in the thigh. Joey’s door knobs would hit me in the ribs. And so on. The net effect was I felt very small. Like I had been shrunk, by a mad scientist. Maybe the aluminium glass people would take it up next.

And I felt slow. Obviously. It took 50 per cent longer to get anywhere. Three steps from A to B was really four and a half. It was like walking through molasses. Or walking backward. Always hustling, and getting nowhere. Like going up the down escalator. Disorienting, like a whole different dimension.

I stopped what I thought was six feet from where the hallway turned. But it could have been nine. Either way I held my breath and listened. And heard nothing. No crunching of broken glass underfoot, and no opening and closing of doors. So I inched towards the corner, or three-quarter-inched, or an inch and a half, or whatever it really was. I had the Browning in my left hand, and the Glock in my right, with one in the chamber and twelve in the magazine. Five rounds expended so far, four under the Jaguar’s hood at Charlie’s house, and one into the bowling club’s subsoil, via Joey.

I figured if Kott was expecting a head to come around the corner, he would be expecting it at normal height, purely as a matter of default instinct. But what was normal? Eye level about five feet six inches from the ground, probably, which was 55 per cent of a normal room’s height. Which would translate to about eight feet three inches in Joey’s funhouse world. Which would mean Kott would be staring way over my head. But even so I played it safe. I made sure he would be staring over my head. I knelt down low and took a look at baseboard level, which because of the millwork’s exaggerated height was perfectly comfortable.

I pictured my brow and my eyes, suddenly visible, but tiny next to the extravagant moulding.

No sign of Kott.

I saw shards of glass on the marble. From the window. I saw closed doors. To parlours, and libraries, and sitting rooms. I didn’t see Kott. Was he behind a closed door? Temporarily, maybe. Or perhaps he had never moved. Perhaps he was still upstairs, in the guest accommodations, patient like snipers were, with his .50-calibre Barrett on a table, aimed directly at the door to the suite.

I thought back to the architect’s blueprint we had seen. The guest suite was in the rear left quadrant of the house. Above the kitchen wing, basically. Up the stairs, and turn right. I stood up again, and checked all four ways, and breathed in, and breathed out.

Then I started up the stairs.

FIFTY-FIVE

THE STAIRS WENT half the way up on the left, and then turned a 180 on a half-landing, and went the rest of the way up on the right. And like everything else in the house they were regular items, but expanded in size, so I had to labour up them, stepping 50 per cent higher than normal each time, lurching forward half as far again as my muscle memory expected, to reach the next stair, and then repeating it all. Plus I was aware the back of my head was about to be visible in the upstairs hallway, through whatever kind of railings or spindles the carpenter had used. Kott could be up there, prone, with his muzzle right in line with the banister. He would get me in the back, just before I stepped up to the half-landing. At a range of about twelve feet. Which was four yards. And I wasn’t made of aluminium oxynitride.

So I hugged the wall, and went up backward, until I could see the second-floor hallway for myself. It was empty. No sign of Kott. I hustled the rest of the way and found myself in what looked like a repeat of the downstairs hallway, except the floor was carpet, not marble. Carpet as wide as a new-mown prairie. I saw a bunch of doors, all of them nine feet tall. A corridor, with more doors. All closed. Two on the left, two on the right, and one dead ahead, in the end wall. Which was the guest suite, I figured. I would be walking straight towards it.

But the advantage of walking straight towards it through a giant’s house was I had plenty of wiggle room. Normally an upstairs hallway would be a narrow field of fire. But 50 per cent extra gave me the chance to stay well off the centre line. Because maybe Kott had something rigged. His gun, pre-aimed, locked down, ready to fire through the wood. Maybe there was an infra-red beam. Or maybe he had X-ray glasses.

But I made it to the end wall, safe, and I pressed myself alongside his door, and I flipped the Browning barrel-first in my hand, and I used it to knock.

I said, ‘Kott? Are you in there?’

No answer.

I knocked again, louder.

I said, ‘Kott? Open the door.’

Which I figured he might. Ballistically it was already open. Either one of us could have fired straight through it. In his case he could have fired straight through anything. If he wanted to aim based purely on sound alone, he could. The walls and the floors didn’t exist for him. He was living in a transparent house.

But he would want to watch. Surely. A guy who put a picture on his wall, last thing he saw at night, first thing he saw in the morning, he would want to watch me take the bullet. He would want to see me fall down. He had probably pictured it every day in yoga class. Visualize your success. He had waited sixteen years. He might open the door.

I said, ‘Kott, we should talk first.’

No answer.

I said, ‘No harm, no foul. You forget about me, I’ll forget about you. We can go our separate ways. You should get over yourself. No need to make a whole big thing out of it. I sent plenty of guys to prison and no one else got so mad about it.’

I heard a creak, and for a second I thought it was the door, but it was in the other direction, at the top of the stairs. In the corner of my eye I saw a child flit by. Real fast. Up the stairs and across the hallway and out of sight. A small boy, I thought. How could Bennett not have told me? Where was the mother? What the hell was going on?

I eased my finger off the Glock’s trigger.

Then the back of my brain said, not a child. Not chubby or bony or elastic. But stiff, and worn, and tense like an adult. A small man, maybe five-seven, running past a balustrade five feet high, in front of baseboards a foot and a half tall, under fifteen-foot ceilings.

Not a small boy.

John Kott.

I tried to call up the architect’s blueprint in my mind. I wanted to see the details. The upstairs hallway ran front to back, from the top of the stairs to a feature window above the front door, and also side to side, towards the guest suite in one direction, where I was, and the other way too, towards a huge master bedroom. Kott hadn’t come my way, and I figured he wouldn’t hang out by the feature window. Why would he? Therefore he was in Joey’s bedroom.

Below me I heard a voice. Bennett, in the downstairs hallway. He called out, ‘Reacher? You OK up there?’

I called back, ‘Get out of here, Bennett. No reas

on for you to be involved.’

I listened for a reply, but I heard nothing more.

I tried the guest suite’s door. It was unlocked. I stepped inside. I looked around. I had seen similar places in hotels, but smaller. Living accommodations, all self-contained. A short private hallway, a powder room, a kitchenette, a living room, with two bedrooms, one to the left and one to the right, both with their own separate bathrooms. The left-hand bedroom was unoccupied. The right-hand bedroom had Kott’s stuff in it. Of which there wasn’t much. A bedroll and a backpack, Nice had guessed, back in Arkansas, and she had been more or less correct. The bedroll was a sleeping bag, and the backpack was a duffel bag, made of scuffed black leather, full of T-shirts and underwear and ammunition.

The ammunition was all either nine-millimetre Parabellum, or .50-calibre match grade. Big visual difference. The handgun rounds looked small and dainty. Like jewellery. The rifle rounds looked like cannon shells from a combat airplane. The cartridge cases alone were four inches long.

I checked everywhere I could think of, and I didn’t find a handgun.

But I found the rifle.

It was under Kott’s bed, in a custom case. A Barrett Light Fifty, the real deal, more than five feet long, close to thirty pounds scoped and loaded. From Tennessee. The price of a used sedan, right there. I kicked the scope out of alignment, which is all I had time to do, and then I hustled back to the hallway.

The blueprint said I had to walk thirty feet, and turn right, and walk twenty feet, and turn left, into some kind of a three-sided anteroom ahead of the bedroom itself. On the plan it would be called a niche or a nook, no doubt. The bedroom door was in the wall facing the hallway. I kept the Browning in my left hand and the Glock in my right, like an old-time gunfighter in a black and white movie. Not that I believed those old stories. I never met a guy who could aim left and right simultaneously. Not well, anyway. Better to focus on the Glock, like it was the only gun I had, and if the Browning happened to blaze away at the same time, unaimed and unsynchronized, then so much the better. Couldn’t hurt.

Die Trying

Die Trying Killing Floor

Killing Floor Persuader

Persuader Tripwire

Tripwire Running Blind

Running Blind Worth Dying For

Worth Dying For One Shot

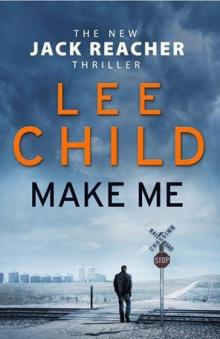

One Shot Make Me

Make Me The Midnight Line

The Midnight Line Bad Luck and Trouble

Bad Luck and Trouble 61 Hours

61 Hours Gone Tomorrow

Gone Tomorrow Night School

Night School Personal

Personal Never Go Back

Never Go Back MatchUp

MatchUp A Wanted Man

A Wanted Man Not a Drill

Not a Drill Echo Burning

Echo Burning Small Wars

Small Wars Deep Down

Deep Down The Hard Way

The Hard Way The Sentinel

The Sentinel The Sentinel (Jack Reacher)

The Sentinel (Jack Reacher) High Heat

High Heat Nothing to Lose

Nothing to Lose The Enemy

The Enemy The Affair

The Affair Second Son

Second Son Without Fail

Without Fail Too Much Time

Too Much Time The Hero

The Hero Blue Moon

Blue Moon The Christmas Scorpion

The Christmas Scorpion The Nicotine Chronicles

The Nicotine Chronicles The Fourth Man

The Fourth Man Deep Down_A Jack Reacher short story

Deep Down_A Jack Reacher short story The Essential Jack Reacher 12-Book Bundle

The Essential Jack Reacher 12-Book Bundle Gone Tomorrow jr-13

Gone Tomorrow jr-13 High Heat: A Jack Reacher Novella (jack reacher)

High Heat: A Jack Reacher Novella (jack reacher) High Heat_A Jack Reacher Novella

High Heat_A Jack Reacher Novella Jack Reacher 15 - Worth Dying For

Jack Reacher 15 - Worth Dying For Jack Reacher's Rules

Jack Reacher's Rules No Middle Name

No Middle Name 14 61 Hours

14 61 Hours First Thrills, Volume 3

First Thrills, Volume 3 Jack Reacher 01 - Killing Floor

Jack Reacher 01 - Killing Floor The Affair: A Reacher Novel

The Affair: A Reacher Novel FaceOff

FaceOff Good and Valuable Consideration

Good and Valuable Consideration Mystery Writers of America Presents Vengeance

Mystery Writers of America Presents Vengeance Jack Reacher 20 - Make Me

Jack Reacher 20 - Make Me Not a Drill: A Jack Reacher Short Story

Not a Drill: A Jack Reacher Short Story 17 A Wanted Man

17 A Wanted Man James Penney's New Identity/Guy Walks Into a Bar

James Penney's New Identity/Guy Walks Into a Bar Vengeance: Mystery Writers of America Presents

Vengeance: Mystery Writers of America Presents Lee Child's Jack Reacher Books 1-6

Lee Child's Jack Reacher Books 1-6 Killer Year

Killer Year Personal (Jack Reacher 19)

Personal (Jack Reacher 19) The Essential Jack Reacher 10-Book Bundle

The Essential Jack Reacher 10-Book Bundle First Thrills

First Thrills Echo Burning jr-5

Echo Burning jr-5 Good and Valuable Consideration_Jack Reacher vs. Nick Heller

Good and Valuable Consideration_Jack Reacher vs. Nick Heller A Wanted Man: (Jack Reacher 17)

A Wanted Man: (Jack Reacher 17) 23 Past Tense

23 Past Tense First Thrills, Volume 4

First Thrills, Volume 4 Small Wars_A Jack Reacher Story

Small Wars_A Jack Reacher Story